“The climate convention wants Africa to reduce CO2, to protect its forest. You impose that, but what is our benefit? In America, in Brazil, forests are cut down to give room to industries, you have work and you are rich. But in Africa, people must protect the forest. However, they do not benefit from that. We are left behind”.

Young man, Socambo*

In light of rapidly declining biodiversity, international policy targets seek to turn 30 % of global territory into protected areas by 2030. Protected areas, however, are not uncontroversial. Violent exclusion of local communities, increasing militarization, and top- down, coercive governance have led to mounting criticism of conservation efforts, and fueled conflicts between parks and local communities.

Despite international debates about appropriate conservation models, there is a serious lack of listening to and understanding local people’s lived experience. What are the hopes, aspirations, and predicaments of people living in or near protected areas?

In 2018, a research team of the SLE explored the challenges and opportunities of Lobéké National Park to effectively conserve its biodiversity and meeting social equity goals. Using qualitative methods such as PhotoVoice and Theatre of the Oppressed, the team explored park management challenges, levels of local stakeholder participation, local livelihoods, and conflicts between park and local people.

Lobéké National Park is located in the heart of the Congo Basin, the “lungs of humanity”. It has been declared a UNESCO world heritage site and is the habitat for a number of critically endangered species such as forest elephants, Western gorillas and grey parrots. Despite conservation efforts, the park suffers from continued species decline and has difficulties effectively protecting its unique natural resources. The park is also accused of depriving local people of their livelihoods and disregarding their basic rights, leading to disputes and conflicts.

“I used to live in a hut like that, and I like them. I stay in a hut like that one when I am working on my fields in the forest, where I plant bananas and cacao. After a week, I will build a new hut”.

PhotoVoice participant (Baka, female)

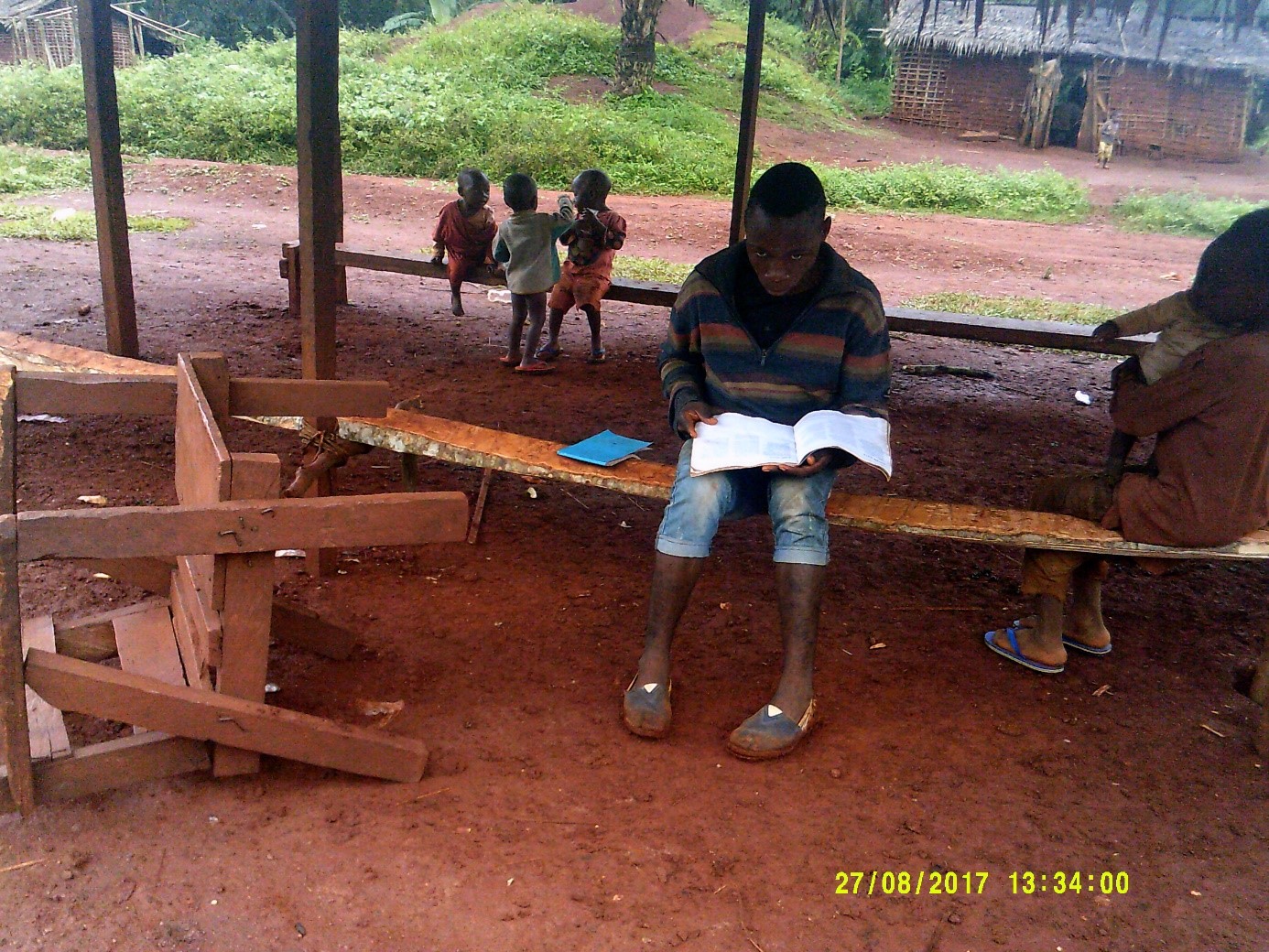

The selected images are based on twenty PhotoVoice interviews conducted in five villages adjacent to Lobéké National Park (Mambele, Salapoumbe, Libongo, Socambo, and Zega). Participants were selected based on their willingness to participate, availability, gender, age, and ethnicity (indigenous Baka or Bantu).

Each participant was given a digital camera for two days. They were asked to take 10 photos of important aspects of their daily lives. After two days, the photos were shared and discussed with the participants.

Here we show a selection of this material, sorted by topic and commented by the participants. The most popular topics discussed were inadequate housing, lack of clean water and sanitation, lack of access to health services and education, food and agriculture, and conflicts over conservation.

Around 23,000 people live in the 28 villages bordering Lobéké National Park. The majority of the local population belongs to the indigenous Baka. For the most part, the people live in extreme poverty. The average annual income is about $150/year. There are very few formal employment opportunities, and people are highly dependent on forest resources (timber, bushmeat, and other forest products) for survival.

People do not have access to basic infrastructure, including health care, schools, and clean drinking water. As a result, the majority of the local population feels abandoned and neglected. This deprivation of basic needs fuels a negative perception of conservation.

The local population is highly dependent on the use of forest resources and access to land for their livelihood. The main activities by which local people earn their livelihoods are hunting, gathering non-timber forest products (NTFP), agriculture, livestock, and fishing. These activities are predominantly meeting subsistence needs.

Neglect of local needs combined with persistent extreme poverty has fueled resentment over the costs of conservation. Symptomatic of this conflict are perceived threats to human safety from wildlife and violent conflicts between eco-guards and local people. In addition, conservation efforts have spurred inter-community conflicts between indigenous Baka and Bantu-speaking groups, and challenge equitable benefit- sharing and participation.

The selected PhotoVoice pictures offer a glimpse into local peoples’ lived realities, revealing conditions of extreme poverty. The deprivation of basic needs might explain the widespread dissatisfaction with the park, which so far offers no tangible benefits to local communities. On the contrary, unclear use regulations, abuse of power by local eco- guards and safari companies, and lack of participation in conservation management further limit their already severely constrained livelihoods. As a result, the park is perceived as an alien construct imposed on the communities, thwarting local development — poignantly captured through statements such as “conservation does not like the people” or “elephants are more protected than humans”.